Weaving Futures: A Conversation with Mika Benesh

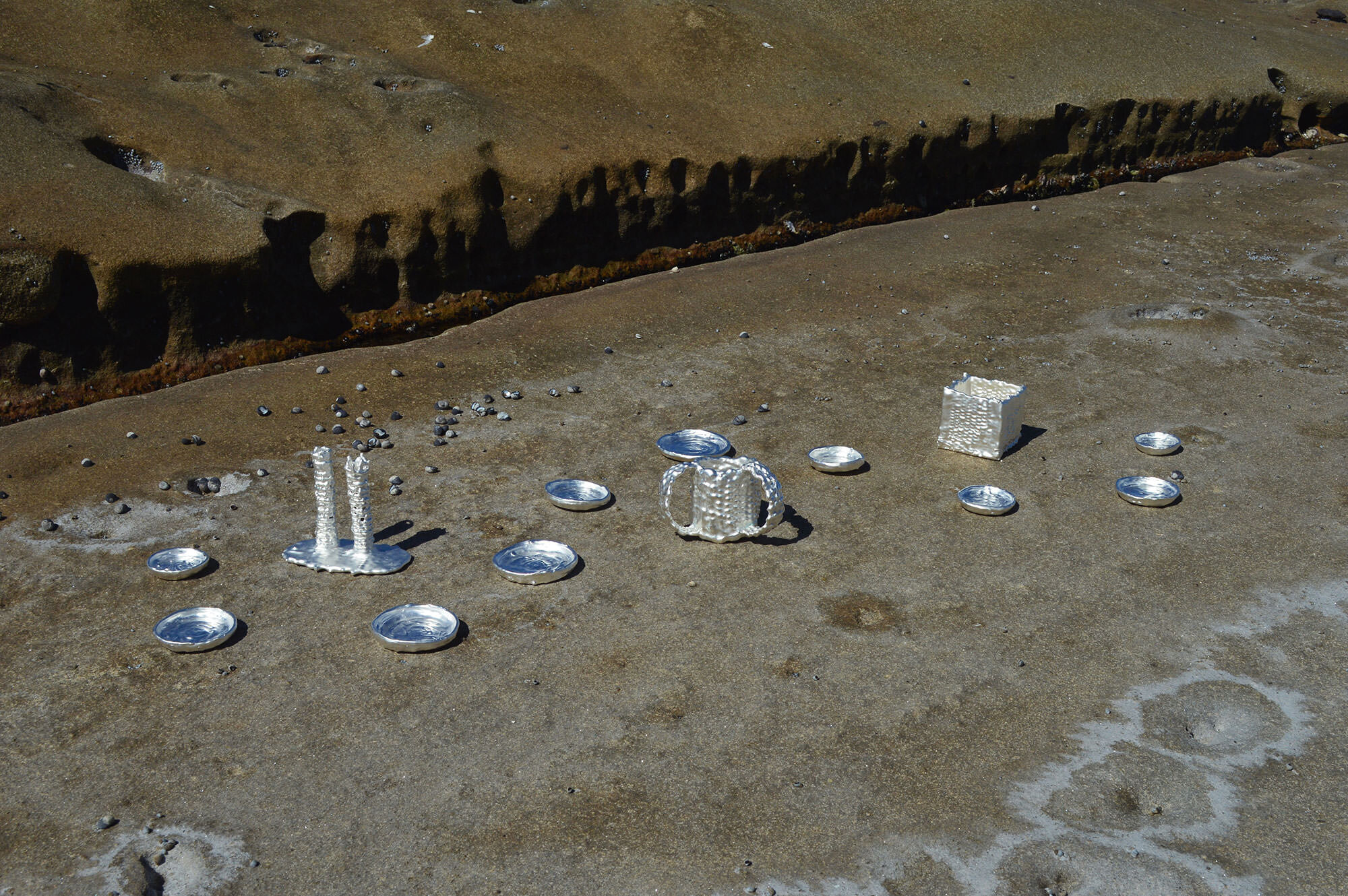

Mika Benesh is an artist, writer and designer currently living and working on Dharug land in Sydney, Australia. A Finalist of the 66th Blake Prize, their Honours thesis project at UNSW Art & Design is titled Weaving Futures. The project comprises a Seder plate, Shabbat candlestick set, a natla (ritual hand washing cup), and a tzedakah box. Having worked in their family apiary business, Mika made the objects out of woven string and beeswax, bronze-cast and silver-plated them. The series contemplates how Judaica objects can be designed for emerging and marginal ritual practices.

ZAMAN Co-Editor Sophie Levy spoke with Mika about the project’s title, its connection to the concept of “Jewish temporality,” practicing Jewish ritual as a trans person, and the value of participatory, inviting design. Sophie Levy: How would you describe your practice? What led you to Weaving Futures?

Mika Benesh: In my work, I tend to trace relationships between cultural institutions and archives, spirituality and theology— especially Judaism— and queer and trans lives and movements, and sometimes also their relationships with white supremacy.

Over the past year or so I’ve been really interested in Judaica design and emerging and marginal Jewish ritual practices, and exploring how to facilitate them through designing Judaica objects.

SL: There’s this larger movement that I’m witnessing through the internet lately, where queer people are questioning or rejecting the notion that their Judaism has to be atheist, has to be secular, has to be devoid of spirituality. Do you think your work stems from an exposure to that discourse at all?

MB: Yeah, I would say so. I’m not a particularly [religiously] observant person, but I think reading about feminist Jewish practices, for example, has resonated really deeply with me. We receive a lot of cultural messages broadly that religion and [feminist, trans-affirming practices] don’t mix, so be able to root my values in these rituals and practice them in a way that connects me to family and a deeper lineage is not just meaningful, it’s nourishing.

SL: I like that you used that word, because it has a much more corporeal connotation than “meaningful.” That’s reflective of your work- it’s not just cerebral; you make physical objects that you hold in your hands, and they’re functional as well as symbolic. Did you always know that you wanted to approach your work that way or is that aspect of design and functional use new for you?

MB: I think for as long as I’ve always been intentionally making things, I’ve always been drawn to things that I can hold and touch. My very first big project at the end of high school was a book, and I wanted people to touch it and look through it. I’ve never really been into making work that you sort of just hang on a wall or can’t touch. So I guess that’s why I feel more drawn to design than fine art making, even though I kind of move between the two.

SL: I think that appreciation of functionality brings a different kind of engagement to the table, where the person who’s interacting with your project becomes more than just a “viewer.”

MB: They become a participant.

SL: Yeah, exactly. What do you think makes that participatory quality particularly important for Jewish art and design in the margins?

MB: My most gratifying experiences of Judaism have always been ones where I was invited to get involved in things, and felt that people wanted to hear participants’ opinions and for them to bring something with them, not ones that felt hierarchically instructive or like some sort of passive cultural osmosis. There’s certainly some of that as well in more institutional Jewish settings, but I’ve never stuck around for long in those spaces. I’m always drawn to ones that actively facilitate that kind of horizontal engagement.

As I kept researching and reading about emergent Jewish rituals and started to practice them myself, I thought, “Well, it’s nice to do this with what I have at home, but what if I were using Judaica that was designed with these rituals in mind? What would that look like?” I just got to a point where I really wanted to investigate the potential for Judaica design to facilitate these practices in a tangible way.

SL: I think what’s effective about your work is that there is this connection to that kind of traditionalism in the glint of the silver casting; it’s like an ode to the old Judaica objects you see in online archives or museums or even your family home.

The beauty of that metallic look kind of reminded me of this short story by Bialik, “The Shamed Trumpet.” He writes from the perspective of a man remembering his childhood in Russia before his family was displaced to the Pale of Settlement— and when he writes about his mother cleaning her Judaica before Pesah, the way he describes the shine of the polished silver has such a beautiful air of holiness to it.

I think we shy away from ascribing that word- “holy-” to material objects in Judaism sometimes, but there is a real meaning to that tactile and visual element of things. Even as you bring a newer voice to the craft, these pieces do still harken back to those deeper feelings traditional Judaic objects can evoke. Do you feel that way about your work?

MB: I think so! And the concept of hiddur mitzvah— of beautifying ritual observance— really affirms my material approach. As much as I’m about challenging conventions, I feel quite a traditional sensibility sometimes when it comes to admiring Judaica. I’m always drawn to the old, fancy stuff. In a way, I think I was trying to find a balanced answer to the question: “How do you make something new that still looks like it [has the soul of] something old?”

There’s a lot of contemporary Judaica that I don’t like. As I tried to parse out what was bothering me about the Judaica I was looking at, I noticed that they all followed the same structural conventions, and there was no rethinking of “Is this what a seder plate needs to look like?”

SL: And I think there’s a way of questioning that without betraying the laws of kashrut, too.

MB: Yes, and even with those laws in mind, I still felt like I had so much flexibility. What I really liked about the [modular] seder plate I made, for example, is that it can be used traditionally, or you can use it in completely unconventional ways, as well. It was really important to me to be able to make works that people could be able to use in whatever way they wanted. I didn’t want to necessarily tell people what to do. I wanted to ask end-users, “Okay, do you want to put something else on there, as well as the traditional stuff? You can if you want.” To design in a way that gives people more options, rather than less. And even just in terms of practicality, I think it’s easier to pass around a series of little plates rather than a huge one. I feel like it just makes sense.

SL: Yeah, there’s something more inviting about that format, about different “parts” of the whole plate being able to go multiple places at once. I also think that sense of flexibility ties in so nicely with the way you describe your interface with Judaism and Jewish life more broadly.

I relate to what you said earlier— even as you’re trying to go about things in a new way, you find yourself gravitating toward the old. I like thinking about Iranian Jewish amulets more than I like thinking about minimalist ‘80s Judaica.

MB: Oh, completely. I’ve been looking at amulets so much lately!

SL: I also think there’s something even… politicized about the act of looking back toward amulets and talismans as legitimately valued objects or parts of Jewish visual culture. Of course, European Jews made amulets too, but I think metallic ones— like the silver you use in your work— were more commonly found in Middle-Eastern communities. And there’s always been this stereotypical accusation that our traditions are “superstitious,” or less legitimate in their understanding of spirituality, as opposed to Ashkenazi ways of life.

MB: Which is hilarious. Have you met Ashkenazim? Like, hello? We’re all superstitious.

SL: [Laughs] Right. So I think not being afraid of investing those artifacts is a statement against the ways we’ve been distanced from rituals either institutionally, or in the case of secularized Israeli families, at the state level. It’s a rejection of the shame we’re pressured to feel around this history of metalwork and talismans.

Back to Weaving Futures— can you talk about the specific techniques you used to create these objects? How and why do they have this woven texture?

MB: Well, when the pandemic started, I lost access to my jewelry studio at uni, so I wasn’t able to hand-forge anything. That was honestly a bit of a relief for me, because I don’t like hand forging; I much prefer working with wax, which then ended up being my only option for my Honours year.

A few years ago, I’d had an idea to make these sculptural havdalah candles, but I never got around to it until I was commissioned to do it last year. While working on that project, I realized that the way I was working with the wax and the woven thread would actually be really good for lost-wax casting, to make metal objects. And it took off from there.

SL: Right, and that method winks at your project’s title, at the idea of weaving a new future. This whole theme of weaving reminds me of Noam Sienna’s book A Rainbow Thread—

MB: —and Judith Plaskow’s book Weaving the Visions.

SL: Yes, exactly. Weaving and threads have become these very common motifs in queer and feminist Jewish media.

MB: It’s funny, because I wasn’t thinking about that when I started my project at all; it was much more about the practical side of the process. And then it turned out that heaps of other people have been thinking about weaving as well, which was really exciting.

SL: I think there’s a labored quality to that woven texture. If they were just smooth, silver surfaces, the pieces wouldn’t have the same air of attention that you can observe in a woven object; they wouldn’t look and feel as personable or complex.

Which one did you enjoy making the most?

MB: I really enjoyed making the Seder plate, but that one wasn’t exactly woven. With those little dishes, I took the string and wrapped it into a flat spiral, and dipped it into hot wax as I went. It was really hard, but it was kind of soothing, too, to sit in front of this boiling pot of beeswax for hours at a time. So that was really fun. But I think I like the way the [ritual handwashing] cup— the natla— turned out in the end the most.

SL: I was so struck by the natla too. What was going through your head when you were making that object in particular?

MB: All these transgender Jewish rituals I had been coming across and starting to practice myself— especially trans mikveh rituals— are interesting because they’re typically written to mark big transition milestones, like changing your name, or starting hormones, or getting ready for a surgery.

But transitioning is also a really everyday event. For example, I don’t take my hormones weekly or fortnightly, I take them every day. And part of that daily process is that I have to wash my hands afterwards. I was also thinking about how Joy Ladin wrote about saying shehecheyanu over her hormones every morning.* So those things made me think about the washing and mikveh rituals in a more everyday sense.

SL: That’s really beautiful. And it’s also very Jewish, I think, to see observance as something that’s about more than sporadic events of monumental scale. So much of Jewish spirituality is about diligently repeated, meditative acts and their incorporation into the everyday sphere, so I think that’s a really eloquent connection to draw between transitioning and Judaism.

MB: I’ve been thinking about that a lot lately— of course, about being Jewish and trans, but also about trans spirituality in general. I think a lot of people would expect us to kind of disavow religion, or shun it. But that’s not really the trend I see. I think many trans people are actually very interested in the spiritual. And that isn’t something that’s commonly discussed in any aspect of trans care, social or medical or otherwise. Even mental healthcare can be so divorced from spirituality, and I just mean spirituality the broadest sense, which can look like anything from connecting with nature to being with your loved ones. It doesn’t have to be institutional or prayer-centered.

SL: Yeah, I just get a more elemental rather than institutional sense from your work and from what you’ve said so far today. How you think about your connection to yourself and your body and water and other people… that mindset can be more welcoming for people who are trans, many of whom may have had a harder time finding a home in mainstream institutional Jewish settings, unfortunately.

MB: Yeah. I know many queer and trans Jews who feel alienated from Jewish institutions, and I've become averse to them for similar reasons. So it’s one of my goals to hopefully start bringing us together in a different way.

The tzedakah box I made is kind of a response to those institutions, in a sly way. Something that really bothers me is that when you’re in a Jewish community space in Sydney, if you see a donation box, it’s almost always designated toward an Israeli organization. I rarely see tzedakah boxes for grassroots organizations or campaigns that are based on this continent, which is frustrating. It shows a real disconnection from our immediate communities.

When I exhibit the tzedakah box, it's an interactive work. Robbie Thorpe, a Gunai / Maar activist, coined the concept of “Paying the Rent,” which is a way for non-Indigenous people living on this continent to pledge a contribution to First Nations peoples as one method of redress for the ongoing occupation of this land.* So when I show the tzedakah box, I select a First Nations organization or campaign that all the donations from the box will go towards, invite audiences to make a small contribution, and I match those donations myself.

SL: That commitment you’re making doesn’t surprise me, only because I feel like your work itself is about much more than lip service. Weaving Futures is a series of actually usable objects, not just inert pieces of matter that profess an idea.

MB: Jewish engagement with acts like Paying the Rent was something I wanted to think about, too. I’d really like to see Jewish communities show greater solidarity with First Nations, and I think it’s helpful to do that in a culturally informed way by linking it to existing Jewish obligations regarding working towards justice and wealth redistribution.

SL: Right, and I think the tzedakah box acts as a very literal enmeshment of First Nations reparations work and this world of emergent Jewish practice you’re cultivating, as well.

MB: I’m really interested in the idea that interrogating / challenging / subverting cultural assumptions and expectations within Judaism can constitute a Jewish tradition in and of itself. Judaism is constantly in flux, constantly undergoing change. The idea that the way we do things now is how it’s “always been done” or “always will be” isn’t accurate. What’s stopping any of us from contributing to that change?

SL: This reminds me of something my friend and havruta Lilinaz Evans, who co-founded Kolot haKahal, the Sephardi Egalitarian Minyan in London, said to me a few months ago. How being Iranian women studying Talmud, completing text study from a feminist point of view, engaging with the same texts rabbanim engaged with centuries ago, is just another rung on this ladder of Judaism, and there’s always going to be room for more of them. Time accommodates more and more room for these stories to be told and retold and reinterpreted.

Heschel wrote about how Judaism comprises both history and philosophy, encapsulates both space and time.* And I think your project does that really effectively. It’s material, it exists in space, but it also facilitates practice and taps into time in a Jewish sense.

MB: I was thinking so much about Jewish temporality with this project, about what it means to think about the future. I remember reading Jasbir Puar’s Terrorist Assemblages, seeing how she wrote from a framework that she called “anticipatory temporality.”* She talked about how we can “invite futurity without scripting it—” and that really clicked for me. I also was influenced by Christina and Thomas Hellstrom, who wrote about the act of imagining the future in a design context, and investing that vision with emotional loading.* I keep coming back to Aurora Levins Morales’ poem “V’Ahavta,”* as well. That’s the kind of emotional investment in the future I draw my strength from.

SL: Something that I’m learning as a student of Jewish history is that only recently have people started to second-guess this conception of Judaism as an entity rooted in the past, as a subject that relates exclusively to words like “memory” and “history.” Based on the way so much Jewish history has been written, it’s as if a notion is furthered that Judaism has elapsed us, and we’re just living in the aftermath of its attempted annihilations. Yes, the act of looking back and remembering is deeply important; it’s a lot of what we do at Zaman. But I hear remembrance and mourning talked about so much more than imagining the future.

MB: I think Judith Plaskow said that new feminist ritual practices transform acts into “living memory,”* which I think is also future-facing, because they are being lived. Norma Joseph, one of my Jewish studies professors when I was on exchange in Montreal, said something that I loved— “when I light Shabbat candles, I’m traveling through time.”

SL: Yeah, that connects back to Heschel, I think. It’s fascinating, this idea that Jewish ritual interrupts the rote linearity of time and makes it so much more multidimensional; that Shabbat places you in a different temporal sphere, a “palace in time.” And when you feel that on Shabbat or on a yom tov or during a ritual, it’s almost overwhelming.

It’s all the more enriching to be able to hold an object in your hands that is so connected to these ideas of Jewish temporality, to looking back and looking forward in simultaneity, and also to the everyday picture of practicing Jewish rituals and living a trans life.

What do you see happening with these objects? Do you want to make more? Who do you see using them?

MB: I would love to make more of these objects, and see people use them! It’s a bit tricky now; they’re solid metal, which is heavy and not exactly practically portable even though they are usable, so I’m hoping to make ceramic versions of them this year, maybe with 3D scanning. I don’t want to make this into a whole business venture that’s just about profit, but it would be really nice to find a way to make these objects more accessible and have a small run of selling them, seeing them go to good homes. I think just about anyone can use these objects, but I’d love to see Jews who practice emerging or marginal rituals using them in innovative ways.

SL: Well, there’s a lot to this project that kind of just bars it from being flatly about profit. It’s life-affirming to see that someone like you is out there doing the work of making Judaica for the future. I hope that in time, we can all have something of yours in our homes.

MB: Ah! That would be a dream.

* Further Reading

Ladin, J. (2012). Through the Door of Life: A Jewish Journey Between Genders (p. 13). University of Wisconsin Press.

Leah, Y., & Thorpe, R. (2018). Pay The Rent. Australian Jewish Democratic Society. Retrieved 25 November 2020, from https://ajds.org.au/2018/03/pay-the- rent/?fbclid=IwAR2LMpqoBi0uiQ9x1w5H1srBYiGKMmMM19XGi4CoxmnjTEezkk8Wx7 6G37o.

Puar, J. (2007). Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times (p. xix). Duke University Press.

Heschel, A. J. (1951). The Sabbath. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. See p. 12: “A Palace in Time”

Hellström, C., & Hellström, T. (2003). The Present is Less than the Future. Time & Society, 12 (2-3), 263-279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463x030122006

Levins Morales, A. (2021). V'ahavta. Aurora Levins Morales. Retrieved 25 January 2021, from http://www.auroralevinsmorales.com/blog/vahavta.

Plaskow, J., & Christ, C. (1989). Weaving the Visions. Harper & Row.