Sarchal: The Forgotten History of Tehran’s Jewish Ghetto

To reminisce is to remember with pleasure, to recollect past events while indulging in the enjoyment of nostalgic return. It would be too simplistic to say that the Jews of Iran reminisce blissfully about their past in a country with a fraught history of antisemitism, yet too harsh to conclude that the calamities they endured ought to completely overshadow their 2500 years of rich history. Memories of Sarchal, the Jewish ghetto of Tehran, serve as living manifestations of this ambivalent train of thought. A dynamic community that was forced to adapt to the ebb and flow of life under monarchical Shi’a regimes, Sarchal was much more than a physical location that housed Iran’s urban Jews from the dawn of the Safavid dynasty through to the troughs of a new Islamic Republic.

In 1588 CE, the Safavid Shah Abbas I revived the Persian empire after centuries of Mongol and Turkic governance. Fairly benign in policy during the first half of his rule, Shah Abbas I reversed his friendly attitude towards the Jewish population when a convert from the city of Lar impelled a royal edict that would force Jews to wear distinctive badges and headgear. Under this edict, Jews were now formally categorized as najjes (ritually impure) under the empire’s Shi’a theocratic law, and ghettoization would begin with the forced expulsion of Jews from Esfahan who refused to convert to Islam. Those who did convert were forced to practice Judaism secretly until 1661, when an edict would allow them to conditionally return to Judaism through payment of the jizya (a tax levied on religious minorities) and wearing their designated badge.

Conditions worsened for Jews during the Safavid era until one of the last kings of the dynasty, Nadir Shah, came to power in 1736 and abolished Shi’ism as the empire’s official religion. This action enabled Jews in cities like Mashhad, who had previously been subject to forced conversion, to reestablish and regrow their communities. Still, neither prosperity nor persecution were experienced by Jews in a linear fashion: the rise of the Qajar dynasty in 1794 spelled the onset of tightening oppression. The Romanian Jewish traveler and historian J.J. Benjamin wrote about the horrid conditions of Jewish life in Qajar Iran in an account from the mid-19th century:

“They are obliged to live in a separate part of town; for they are considered as unclean creatures… Under the pretext of their being unclean, they are treated with the greatest severity and should they enter a street, inhabited by Mussulmans, they are pelted by the boys and mobs with stones and dirt… For the same reason, they are prohibited to go out when it rains; for it is said the rain would wash dirt off them, which would sully the feet of the Mussulmans.”

Given the Jews’ status as a najjes group, the most straightforward way to limit physical contact between Muslims and Jews was to segregate them geographically. In Iranian cities with high Jewish populations like Esfahan, Kashan, Tehran, and Hamedan, Jews were segregated into designated neighborhoods, sometimes within the main city walls and sometimes outside of them. The internal layout of each mahaleh (ghetto) played an important role in distinguishing Jewish life in Iran from the history of other ethno-religious communities.

One such mahaleh was Sarchal, the Jewish quarter of Tehran. Sarchal was different from other Jewish ghettos in Iran given its location in the nation’s capital city of Tehran, an especially volatile and ever-transforming urban enclave since its founding by Qajar King Agha Mohammad Khan in 1786. Unlike the ghettos of Esfahan and other cities, Sarchal was located within Tehran’s old city walls. It is also unique in its oxymoronic overlap with a network of mosques and its proximity to a center of commerce, Tehran’s grand bazaar. Jews and Muslims in Tehran therefore must have interacted very frequently despite the Qajar regime’s heavy-handed, active efforts to quarantine and suppress Jewish life under their rule.

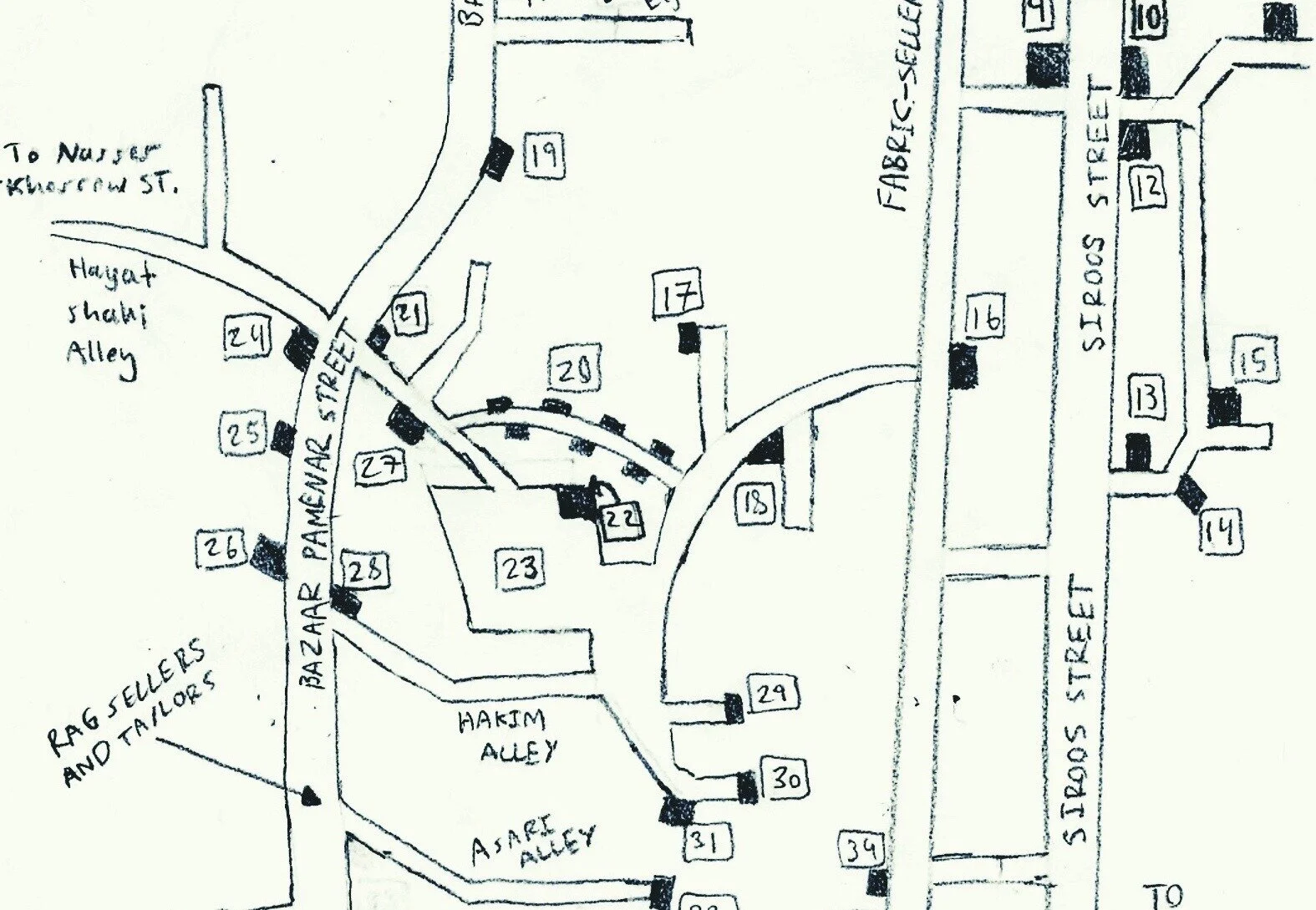

Sarchal is situated in the southeast corner of old Tehran, contemporarily known as the 12th district. It is directly west of Emamzadeh Yahya, or the birthplace of Imam Yahya, north of Tehran’s grand bazaar, east of Pamenar Bazaar, and south of the Qajar era Masoudieh palace (Map 1). I have also included below a map in Farsi created by Eshaq Shaoul that highlights landmarks, religious structures, and other important sites in the ghetto (Map 2). I have translated his map and included a key identifying the aforementioned sites in English (Map 3).

*Scroll to the bottom for a typed key to Map 3

Very few of Sarchal’s original structures remain intact today. The “Seven Synagogue Alley,” an alley literally surrounded by seven synagogues behind Sarchal’s main plaza, is now nowhere to be found. All the old Jewish hammams (bathhouses), which were built because Jews and Muslims were not allowed to use the same public baths, are gone, as are the Jewish butcher shops, bakeries, and zoorkhanehah (gymnasiums). The Ezra Yaghoub and Mullah Haninah synagogues are still standing, along with Sapir hospital, Pamenar Mosque (dating to the late Sasanian period), Abol Hassan Mosque, Haj Ali Khan Mosque, and Ayatollah Shah Abadi Mosque.

Street names were also changed following the Islamic Republic regime’s campaign to erase historical and cultural remnants of the Pahlavi era, often replacing them with the names of Shi’a religious and revolutionary martyrs. Cheragh Bargh Street is now Amir Kabir Street, Siroos (Cyrus) Street is now Mostafa Khomeini Street (commemorating Khomeini’s son who died before the 1979 revolution), while Pamenar Bazaar street endured little change and is now Pamenar street (Map 4).

Map 4 Key:

16. Abol Hassan Mosque

23. Sarchal Plaza

24. Pamenar Mosque

29. Ezra Yaghoub Synagogue

5. Ayatollah Shah Abadi Mosque

8. Birthplace of Imam Yahya (Emamzadeh Yahya)

10. Sepir Hospital

12. Mullah Haninah Synagogue

Sarchal originally included every necessity for Iranian Jews to conduct Jewish life in an incredibly small quarter with an area of less than one square mile. On an average day, one could stop by the bakery to pick up bread, visit the yogurt maker or butcher to prepare a meal, exercise at the zoorkhaneh, pray and study at one of nine synagogues, buy medication from either of two local pharmacies, and engage in scholarly life by buying a book from the bookstore. Reminders of a bygone era of Jewish life in the ghetto are echoed in prominent family names like Dardashti, Torbati, Elghanyan, and Hakim that originated in Sarchal, as well as the titles of surviving architectural spaces: “rag seller and tailor” alleyway, “welder’s bazaar,” and “cannonball storage facility.”

Slowly but surely, the massive discrimination of Iranian Jews that kept them ever close to one another in the confines of the mahaleh would reduce to subtlety after Reza Shah Pahlavi came to power in 1925. The official categorization of Jews and other religious minorities as najjes would be abolished, and the political power of the Shi’a clergy greatly weakened, ushering in a new zeitgeist marked by relative religious tolerance, which the Iranian Jewish historian Habib Levy would call “The Golden Age of Iranian Jewry.” Beginning in the 1940s and bleeding into the 1950s, the last remaining Jewish families of the mahalehs of many Iranian cities left their communities of origin for better jobs and assimilation in Northern Tehran. The Jewish communities of Iran– and with them, Sarchal– would eventually see their quasi-extinction after the 1979 Revolution, when the vast majority of Jews were compelled or forced to flee their home of 2500 years due to the new wave of institutionalized antisemitism established by the world’s first parliamentary theocracy, The Islamic Republic of Iran.

Whether you read The Proverbs of John Heywood from 1562 or listened to Snoop Dogg’s album “I Wanna Thank Me” from 2019, we are all well aware of the phrase “let bygones be bygones,” but to what degree does this sentiment merit acceptance in the context of Iranian sociopolitical history? As far as Jewish Iranians like me are concerned, forgetting the past can be detrimental to the continuation of our existence. There is a stigma surrounding the word Sarchal; many Persian Jews are reluctant to admit our history of poverty and ghettoization. But anything short of active remembrance would serve as a disrespectful gesture to the rag sellers, fabric dealers, grocers, midwives, homemakers, rabbis, butchers, dairymen, and tailors that made life in ghettoes like Sarchal sustainable and even vibrant, not to mention the Muslim business owners and civilians who continued to associate with Jewish communities despite institutional restrictions that prohibited them from doing so.

Jewish Iranians’ eventual outmigration from the mahalehs was surely a turning point that bolstered their financial success in later years and decades, but our escape from oppression should not negate our responsibility to honor our ancestors who built lives within its confines. In fact, we have much to learn from the Sarchalis who managed to raise families, provide for their community as a whole, and motivate Jewish life in less than one square mile– with all the odds stacked against them.

18. Bookstore

19. Fereshteh Pharmacy

20. Seven Synagogue Alley

21. Eshagh’s second house

22. Sarchal Bathhouse

23. Sarchal Plaza

24. Mosque

25. Morteza Navi Butchershop

26. Hakim Moshiah Bathhouse

27. Hakim Synagogue

28. Torbati Pharmacy

29. Ezra Yaghoub Synagogue

30. Eshagh’s birthhouse

31. Dekhantal house

32. Dardashti’s house

33. Bakery

34. Yogurt Maker

35. Tekiyeh Mosque

36. Zoorkhaneh

*Map 3 Key:

1. Tamadon School

2. House of Seyed

3. Pamenar Gym (zoorkhaneh)

4. Midwife Zivar’s house

5. Mosque

6. Eshagh Bathhouse

7. Reza Goli Khan Mosque

8. Birthplace of Imam Yahya (Emamzadeh Yahya)

9. Mosque

10. Sepir Hospital

11. Midwife Sabia’s house

12. Mullah Haninah Synagogue

13. Aghajan Bakhshi’s house

14. Chaim Golabgir’s house

15. Ayatollah Behbahani’s house

16. Mosque

17. Ezra Mikhail Synagogue

References

Bentley, Jerry H, and Herbert F. Ziegler. Traditions & Encounters: A Global Perspective on the Past. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011. Print.

Fischel, Walter J. “The Jews of Persia, 1795-1940.” Jewish Social Studies, vol. 12, no. 2, 1950, pp. 119–160. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4464868. Accessed 10 Jan. 2020.

Foltz, Richard (2015). Iran in World History. New York: Oxford University Press.

Levy, Habib (1999). Comprehensive History of the Jews of Iran. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers.

Lewis, Bernard. The Jews of Islam: Updated Edition. REV - Revised ed., Princeton University Press, 1984. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wq0nq. Accessed 10 Jan. 2020.

Sanasarian, Eliz (2000). Religious Minorities in Iran. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shaoul, Eshagh. “Sarechal.com…. Come Home to the Place You Came From.” Welcome to Sarechal, Eshagh Shaoul, http://sarechal.com/.

Tsadik, Daniel. “JUDEO-PERSIAN COMMUNITIES v. QAJAR PERIOD (1).” Encyclopædia Iranica, XV/1, pp. 108-112 and XV/2, pp. 113-117, available online at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/judeo-persian-communities-v-qajar-period. Accessed 10 Jan. 2020.

Vladimir Minorsky. “The Turks, Iran and the Caucasus in the Middle Ages.” Variorum Reprints, 1978.